Spinal Issues Affecting the German Shepherd Dog

The German Shepherd breed is characterized by an efficient structure that utilizes a slightly longer back as a suspension system during movement, particularly at the trot. While this slightly longer back does work effectively as this energy transfer system, it does predispose the German Shepherd Dog to back troubles. These issues range from something as simple as a subluxation of the spine to more severe conditions like genetic Degenerative Myelopathy or cauda equina. In this blog, we will cover subluxations, back strains, spondylosis and transitional vertebrae. In our next blog, we will cover the more serious conditions of cauda equina and degenerative myelopathy.

The German Shepherd breed is characterized by an efficient structure that utilizes a slightly longer back as a suspension system during movement, particularly at the trot. While this slightly longer back does work effectively as this energy transfer system, it does predispose the German Shepherd Dog to back troubles. These issues range from something as simple as a subluxation of the spine to more severe conditions like genetic Degenerative Myelopathy or cauda equina. In this blog, we will cover subluxations, back strains, spondylosis and transitional vertebrae. In our next blog, we will cover the more serious conditions of cauda equina and degenerative myelopathy.

Subluxation

A subluxation is a misalignment of one or more of the spinal vertebrae. Subluxations can have a profound impact on the dog in multiple ways: restricting joint movement and range of motion, creating excessive joint motion (hypermobility), pinching or impinging nerves that exit or enter the spine, tightening and straining muscles, creating abnormal gait and movement, restricting overall motion and flexibility, and more. In some cases, subluxations can even can cause sudden or chronic lameness. Any sign of lameness should be investigated by a vet, of course. But common lameness associated with subluxations include sudden rear end lameness, such as a swinging or ‘gimping’ of the back leg, or moving very stiffly in the rear. Other symptoms include back pain, which often manifests itself as difficulty laying down and/or rising, restlessness or inability to get comfortable, and stiffness or even immobility upon getting up from a prolonged resting position (such as after sleeping).

For our athletic and active working dogs, a subluxation can cause systemic effects on their performance. The misaligned vertebrae can put excess pressure on nerves, which will in turn negatively affect the region innervated by this nerve. The dog may begin to adapt their posture and their movement to compensate for any tension or pain caused by the subluxation, which then creates uneven muscle development, muscle recruitment, and overcompensation resulting in fatigue and even injury of the muscles now taking the load. Excessive movement of the vertebrae can also result in the development of osteoarthritis, creating bone spurs, bridging, and eventually spondylosis. Impingement on the nerves can also alter nerve function, and can cause inflammation as well.

This photo on the right shows the spine of a 7-year-old working German Shepherd Dog who has competed for five years in IPO, and who received regular adjustments from a canine chiropractor throughout his career. A subluxation can be shown at the junction between the last lumbar vertebrae and the sacrum (by the pelvis), but other than this, the spine is in remarkable condition for this working dog. This particular subluxation manifested itself as lower back soreness, shortened range of motion of the rear limbs, and twice as sudden lameness of the left rear leg. Regular chiropractic care coupled with cold laser therapy helped improve and correct this condition.

Back Strains

Dogs can pull the muscles that run along their spine. Actions like running and twisting in mid-air to capture a bouncing ball or Frisbee or fleeing helper in protection work can strain the back muscles. These muscles can also tighten and shorten, losing their suppleness and creating restrictions in the range of motion on one side. This often manifests as the dog clearly favoring one side over the other, and showing an inability to turn or stretch to one side. Back strains cause inflammation in the muscle tissue, which will cause pain and tenderness. Dogs may have difficulty laying down, may refuse to jump, or may vocalize upon jumping, laying down, or stretching. However, because dogs are excellent at hiding injuries, back strains may go unnoticed unless the handler is very astute.

Transitional Vertebrae

Transitional vertebrae are more common in German Shepherd Dogs than in many other breeds. Transitional vertebrae are a congenital malformation of the spine that occur at the junction between either the thoracic and lumbar junction, or the lumbar and sacral junction. In GSDs, the lumbosacral junction is most commonly affected. The transitional vertebrae often will not have any clinical signs associated with it, and many owners do not even know that their dog has a transitional vertebrae until they have the dog’s hips x-rayed for OFA or SV hip certifications.

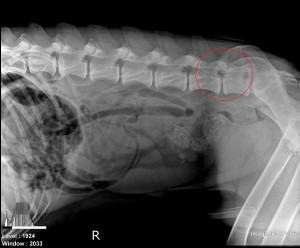

While many dogs with a transitional vertebrae can show few, if any, problems, the transitional vertebrae can create further instability in the lumbosacral region of the spine, increasing the risk of hip dysplasia, spondylosis, arthritis, and even cauda equina (vertebral stenosis). This instability results in excessive movement of the lower region of the spine, which in turn can lead to the development of arthritis and spondylosis. The asymmetry and rotation of the pelvis that can result from a transitional vertebrae has also been implicated in the formation of unilateral hip dysplasia; this can be seen in the x-ray on the left. The transitional vertebrae is circled in red. There is significant asymmetry of the pelvis (seen with how uneven the iliac crests (top edges) of the pelvis are), coupled with unilateral hip dysplasia seen on the left side of the x-ray (original image can be found here).

While many dogs with a transitional vertebrae can show few, if any, problems, the transitional vertebrae can create further instability in the lumbosacral region of the spine, increasing the risk of hip dysplasia, spondylosis, arthritis, and even cauda equina (vertebral stenosis). This instability results in excessive movement of the lower region of the spine, which in turn can lead to the development of arthritis and spondylosis. The asymmetry and rotation of the pelvis that can result from a transitional vertebrae has also been implicated in the formation of unilateral hip dysplasia; this can be seen in the x-ray on the left. The transitional vertebrae is circled in red. There is significant asymmetry of the pelvis (seen with how uneven the iliac crests (top edges) of the pelvis are), coupled with unilateral hip dysplasia seen on the left side of the x-ray (original image can be found here).

Spondylosis

Spondylosis is a common form of arthritis in older dogs, particularly those who have been very active over their lifetimes. With spondylosis, new bone is created on the underside of the vertebrae, and can eventually form across the gap between two vertebrae (a condition known as “bridging”, seen in the image above on the underside of the spine). Spondylosis usually forms in response to instability of the spine, as the body tries to strengthen the spine by fusing the vertebrae. Thus, this condition most commonly forms in the regions of the dog’s spine that have the greatest instability: the lumbar and lumbosacral region, and the thoracolumbar junction. The bone spurs of spondylosis can be quite painful to the dog, and reduce the overall flexibility of the spine. Inflammation from the developing bone spurs can cause pain and stiffness, making it difficult for the dog to lay down comfortably for long periods of time, and to rise upon laying down. Spondylosis can often be managed well with a combination of regular chiropractic care, cold laser therapy, nutraceutical support (glucosamine, chondroitin, etc.), and anti-inflammatories (conventional or alternative) as needed.

Spondylosis is a common form of arthritis in older dogs, particularly those who have been very active over their lifetimes. With spondylosis, new bone is created on the underside of the vertebrae, and can eventually form across the gap between two vertebrae (a condition known as “bridging”, seen in the image above on the underside of the spine). Spondylosis usually forms in response to instability of the spine, as the body tries to strengthen the spine by fusing the vertebrae. Thus, this condition most commonly forms in the regions of the dog’s spine that have the greatest instability: the lumbar and lumbosacral region, and the thoracolumbar junction. The bone spurs of spondylosis can be quite painful to the dog, and reduce the overall flexibility of the spine. Inflammation from the developing bone spurs can cause pain and stiffness, making it difficult for the dog to lay down comfortably for long periods of time, and to rise upon laying down. Spondylosis can often be managed well with a combination of regular chiropractic care, cold laser therapy, nutraceutical support (glucosamine, chondroitin, etc.), and anti-inflammatories (conventional or alternative) as needed.

Stay tuned for our next blog, in which we tackle Degenerative Myelopathy (DM) and cauda equina.